Unfortunately, this risk from psuedoscientific experts making false promises appears to be a rising trend in the Dercum’s Community. It’s come to our attention that there are certain individuals who are posing as Dercum’s experts, specifically to charge incredibly high fees for consultations, all while promising faster diagnostics, radical cure-all treatments, and supposedly offering greater insight into the disease. We don’t want to see anyone fall victim to this trend, spend unnecessary money, or worse, be harmed by any of these radical treatments. We’re determined to do everything we can to help arm you with information so you can protect yourself and your families from falling victim to false experts.

There’s one simple, surefire way to tell a charlatan from a real expert. Before you pay big bucks or accept the word of an “expert”, we want you to ask one question: where’s the evidence? Specifically, has this expert actually conducted any medical research whatsoever?

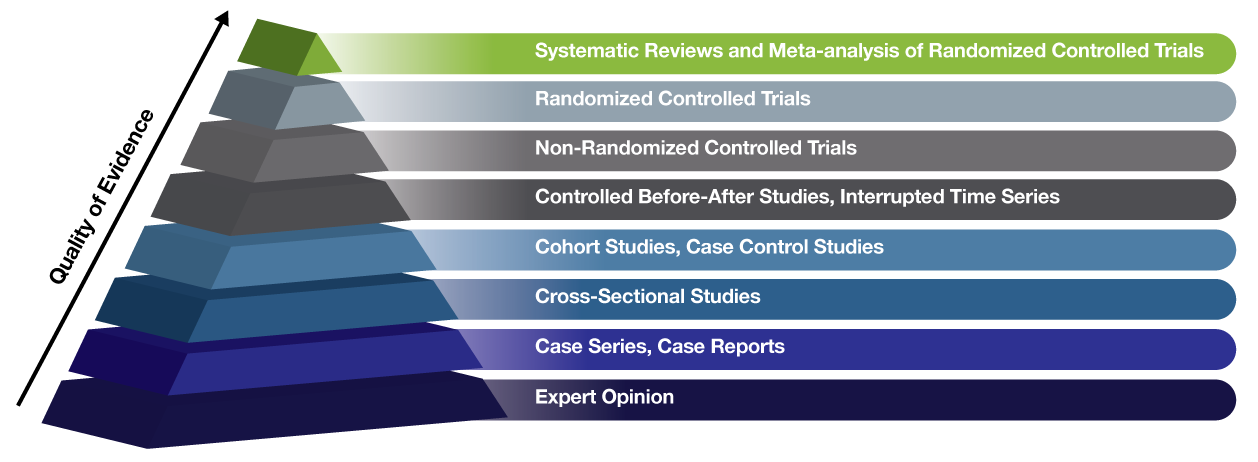

In order to answer that question, it’s important for you to know how to recognize the various types of medical research and how they rank in terms of importance and quality. With that in mind, check out this industry standard chart known as the Evidence Hierarchy. It’s a simple pyramid that shows types of medical research, ranked by the quality of the evidence they provide. Basically the higher up on the pyramid, the less likely the study is to have bias and the more likely it is to provide solid evidence and answers.

We’ve already lived through the dangerous era of “expert” opinion-based medicine, which is what led to such disasters as bloodletting, leeching, and trepanning. That was an era known as Eminence-based Medicine. Thankfully, after too many people died from having holes drilled into their heads for no reason, we moved on to Evidence-based Medicine. Which is where research comes in and why it’s so important. It’s what keeps us from falling victim to dangerous, unproven whims. Dangerous medical myths like trepanning are not a thing of the past. They’ve simply changed appearances. Now instead of things like leeches, we’re manipulated by con artists and self-proclaimed “experts” who trick us into trying radical treatments like altitude chambers and coffee enemas. It may look different, but they’re still just as risky and just as deadly.

If you’ve come across a self-proclaimed expert, look into their background. How much research have they conducted? What types of research did they conduct? How far up the Evidence Hierarchy did their research go? Have they worked on any Randomized Controlled Trials, the gold-standard of research? Or are they stuck too close to the very bottom of the pyramid, in the realm of nothing but “expert opinion”? Your life may depend on how well you’re able to differentiate between pseudoscience and actual research.

A Specific Example in the Dercum’s Community

To give you a better idea, let’s explore one specific example. There’s one “expert” we’re aware of who’s charging between $500 and $1,000 for an initial consultation, promising to speed up the Dercum’s diagnostic process by simply feeling your fat. They promise treatment and pain relief thanks to radical treatments not even performed in hospitals. Their promises are grand, the stuff every Dercum’s patient dreams of.

Yet if you look into their background, what you’ll find is less than impressive. Their claim to “expertise” is based on a handful of patient surveys and a single case series.

Note, patient surveys aren’t even included on the evidence hierarchy. They aren’t even considered research. Why? Because surveys are based entirely on memory recall and patient-supplied information, with no cross-checking against medical records. As we all know, human memories are imperfect. Worse yet, if the medical information isn’t coming from medical professionals or test results, there’s no way to know if that information is accurate or scientifically valid. Hence why surveys aren’t even on the Evidence Hierarchy.

As for the one case series, it was a review of patients utilizing that bizarre treatment not even performed in a medical setting or used by hospitals. No details were provided as far as standardized procedures or reporting methods; a huge no-no in the world of scientific research, where all methods should be presented so they can be repeated to verify validity. Worse yet, the doctor fails to mention in the review that they have a financial interest in the company behind the treatment being reviewed. As if that wasn’t bad enough, we’re also aware of several patients who participated in that review, yet their negative outcomes were not mentioned. People suffered serious, painful, life-long complications, but you won’t hear about any of that in the glowing, all-positive case review. Not exactly scientific or even remotely ethical.

Suffice it to say, there’s no evidence – no actual work – to back up this individual’s claims of expertise. No actual expertise to warrant big fees and even bigger promises. Yet people still flock to them, understandably desperate for help. For relief.

If It Sounds Too Good To Be True…

We all wish there was a faster way to be diagnosed accurately. We all wish there was a cure to rid us of the awful pain and difficulty that comes from Dercum’s Disease. But if nothing else, please always remember this all too important axiom – if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. When it comes to medical issues, there’s an added risk there. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is, and it might just hurt you in the process.

Please, as we know better than most, health is precious. When your health is already fragile, it’s all the more precious. Protect it. Don’t fall victim to self-proclaimed experts making big promises with even bigger price tags. The legitimate medical experts of the world aren’t out to make a buck. They’re out to help people.

If you’d like additional information about the definition of each of these types of studies, click each title below to learn more. We hope you’ll also keep an eye out for our upcoming video series! We hope it’ll help to summarize topics like these, so that hopefully we can help an even wider audience.

Expert Opinion

Case Series, Case reports

The strength of case reports is that they are often the first step in identifying new disease. In fact, research into Dercum’s Disease began this way. Over 100 years ago, Dr. Francis Xavier Dercum first identified what would come to be known as Adiposis Dolorosa in a case report, followed by a case series. However we didn’t really learn anything significant or actionable until further research was done using study types further up the pyramid.

The negatives of case reports and studies are many. Most importantly, the lack of a control group against which to compare for potential biases or abnormal variations in data. There’s also no real way to know for certain any specific causes or subsequent results, since there’s no way to eliminate variables that could influence data and outcomes. Therefore case studies are at the base of the pyramid, nothing more than an interesting start to a much longer and more rigorous study process.

Cross-Sectional Studies

Cohort Studies, Case Control Studies

A Case-Control Study is a type of observational study in which two existing groups differing in outcome are identified and compared on the basis of some supposed causal attribute. Case-control studies are often used to identify factors that may contribute to a medical condition by comparing subjects who have that condition/disease (the “cases”) with patients who do not have the condition/disease but are otherwise similar (the “controls”). They require fewer resources but provide less evidence for causal inference than a randomized controlled trial.

Controlled Before-After Studies, Interrupted Time Series

Interrupted Time Series studies attempt to detect whether a given treatment has had an effect greater than any underlying trend over time. An advantage of this study design is that it allows for investigation of potential biases in effect estimates, including trends over time; i.e. increases or decreases in a health condition with time. For example, if a health condition is increasing before the treatment being evaluated has been administered, a before-after study would have found an increase in the outcome that might wrongly have been attributed to the treatment. An important limitation of interrupted time series studies is that it is often difficult to be sure that the treatment occurred independently of other changes over time and that the outcome was not influenced by other confounders.

Non-Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized Controlled Trials

Random allocation ensures that each participant has a known (usually an equal) chance of being assigned to any given group. This results in treatment comparison groups that are similar in terms of prognostic variables, whether or not these have been recognised. Thus, there is generally a lower risk of allocation bias in randomized studies than there is in non-randomized studies.

These tests are considered the gold standard of medical research because of their strict controls and careful prevention of potential variables that might influence the collection and analysis of data. However, even randomized control trials can be faulty. A study is only as good as its careful design. It’s for this reason that it’s vitally important that researchers carefully detail their study methodology, so that other researchers can then attempt to repeat the study to see if the results remain constant. If the results remain constant across multiple trials, they’re more likely to be accurate.

This is why medical research is such a painstaking, time-intensive, and expensive process. Yet it’s vitally important that time is taken and no shortcuts are taken.

Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis is the statistical synthesis of data from separate but similar (comparable) studies, to generate a quantitative summary of the results overall, including an overall (average) effect estimate, the confidence interval for that estimate, and a measure of how inconsistent (heterogeneous) the effect estimates from the individual studies are. Meta-analysis is often used in systematic reviews but is not a necessary component of such reviews.

These reviews of studies are excellent at finding averages of information, leading to a greater understanding of the validity of previously studied data and outcomes. However, as with all studies, reviews and analyses are only as good as the data being used. If they’re analyzing data from flawed studies, naturally the analyzed averages will be flawed as well.